Assateague's northern tip, from the Maryland State Park to Ocean City Inlet, September 25, 2010

From Assateague State Park to the Dune Trail, April 2, 2011

Along Toms Cove to Assateague's southernmost point, April 3, 2011

This night on Assateague feels like a middle way, like a crossroads. It’s just past the autumn equinox, which coincided with the full moon this year. So the moon is just past the full, with Jupiter nearby it like a spark thrown out of a fire, though of course the giant planet could swallow the moon without a ripple. The island itself is of course a crossroads between worlds, the human and the natural, the express train of the waves and the minor-key symphony of autumnal crickets. Just went out to look at the waves—it’s almost midnight, the moon high in the sky, bright enough to cast shadows. Glint of moonlight on the white breakers.

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Watched the sun rise. The moon had spun over on its back in the western sky by dawn. Below it, the western horizon was all layers of soft pink and lavender. The eastern horizon, over the sea, was swathed in a dense blanket of sullen grayish purple, so much so that I thought I was seeing clouds that would hide the sunrise. But, it wasn’t so. Right on schedule at about ten minutes before seven, a gaudy fluorescent pink triangular wedge suddenly poked above the horizon. It seemed to have straight edges and almost to come to a point at the top. But it changed shape rapidly as more of the distorted, flattened solar disk emerged from the sea. It always amazes me how at sunrise or sunset you can watch the sun’s progress, and thereby indirectly the earth’s rotation, in “live” motion, as it were. There was a stiff breeze up when I set up my tent last night that has now dropped. Yesterday’s unseasonable heat is predicted to be a little milder today, and right now there is a delicious cool. A line of gentle twittering birdsong has joined the now somewhat subdued cricket chorus.

A small, light gray bird with large black eyes sat in the bushes and kept me company through breakfast. (I am really going to have to learn the birds’ names if I am going to become an accomplished Assateaguer!) The campsite, which looked stark and deserted by moonlight last night, reveals itself in the morning in its colorful Assateague glory. Goldenrod is about to burst into bloom, and there is a low plant with red leaves mingled in among the other, greener low scrub. Coming back from Shabbat morning prayers on the beach, I saw a crab no more than half an inch long and perfectly camouflaged light gray like the sand scittering along beside me.

It is oddly appropriate I should have gone tent camping now, in the midst of the weeklong Jewish holiday of Sukkot, the Feast of Tabernacles. It is traditional to build elaborate backyard lean-tos during this holiday, as a memorial of our ancestors the Israelites’ forty years of wandering in the desert. These lean-tos are roofed with pine branches, from which people hang gourds and other reminders of the autumn harvest. Here too the signs of autumn, like that goldenrod, are starting to make their appearance, despite the unreasonable, unseasonable heat.

Today I plan to walk the five and a half miles from the Assateague State Park parking lot to the Ocean City Inlet and back again. The map in William H. Wroten, Jr.’s useful little book Assateague (really more of a lengthy pamphlet at 56 pages) designates this section of the island as Sandy Point and Inlet Shallows. The water separating the island from the mainland of Delmarva in this area is known as Sinepuxent Bay, a wonderful pungent name that looks as if it should be a Latin word, but is no doubt a corruption of some Nanticoke Indian word.

"On Assateague Island, I found, admiration came easily from the moment of my arrival," writes the late Charlton Ogburn, Jr. in his remarkable book The Winter Beach, which I knew and loved long before I read Thoreau’s Walden. It takes no effort at all to maintain this admiration, even with the mosquitos up and actively biting.

Sandy Point, 11 a.m. September 25

I am afraid I do not have the strength of character of Thoreau with regard to collecting. In the first chapter of Walden he writes, “I had three pieces of limestone on my desk, but I was terrified to find that they required to be dusted daily, when the furniture of my mind was all undusted still, and threw them out the window in disgust.” But me, I was delighted to find two whole knobbed whelk shells, one big and blue and one smaller and a mottled brown, on the beach just now, and was unable to resist adding them to my knapsack. But surely Thoreau was right that material clutter inevitably produces a cluttered mind. In preparing to sell our condominium my wife Jackie and I had to get rid of many things and put much else, including most of my books and beloved Assateague whelk shells, in storage. And I find I do not miss them, mostly, which leads me to wonder why I collected them in the first place. Part of the attraction of the seashore is that it is a supremely uncluttered place, washed every moment by the ocean and scoured by the wind. As the body finds few impediments here, so is the mind freed to wander where it will, outside the tracks of ordinary daily life.

It is remarkable, by the way, that I was able to look up the quote from Walden in moments, without having the physical book with me (packed away in storage, I found when I went looking for it yesterday). I used my Blackberry to look it up on the Internet, wondering as I did so what Thoreau would have made of this technology. Contrary to popular caricature, he was not a Luddite; earlier in the same chapter of Walden he writes, “Old deeds for old people, and new deeds for new. Old people did not know enough once, perchance, to fetch fresh fuel to keep the fire a-going; new people put a little dry wood under a pot and are whirled around the globe with the speed of birds, in a way to kill old people, as the phrase is.” True, elsewhere he disparages the freshness of berries carried by train, and he would surely have been horrified by the fact that our devices allow us to be “reached” anywhere, even on a wild island. (Aside from which, his constant disparagement of “old people” is one of the least attractive aspects of Walden, and one wonders how he might have revised his views if he had been granted another thirty or forty years on this earth. Myself, I have the unhealthy habit of measuring my lifespan against those of writers of the past as a way of measuring, as Tom Lehrer put it satirically, how little I’ve accomplished. At forty-one I am only four years short of Thoreau’s age when tuberculosis took his life. And yet, one hundred fifty years dead Thoreau is more alive to me than many living people I have met.)

Further north, in the Inlet Shallows, evidence of overwash is everywhere, dry ripples of tawny sand alternating with troughs composed of a darker, almost charcoal-colored sand. Here, where even the bravest of new dunes with their sharp green plugs of dunegrass to hold them in place stand only a few feet above the mean high tide line.

1:20 p.m., Ocean City Inlet

Approaching the inlet, ghostly white dust devils of fine sand dance in the southerly breeze before me, leading me onward to the north. The slope of the shoreline becomes more and more shallow until it is almost flat, and it looks as if the waves are going to stage a frontal assault on the island and wash over it right before my eyes. Large, sinister flocks of gulls seem unconcerned by this prospect, however, waiting patiently for prey to come their way. At the tideline, a tiny burrowing clam less than a quarter of an inch across digs frantically into the wet sand at my approach. I pass through a field thickly strewn with whelk shells and think to myself defensively, as I bend down to collect them, of the variety of colors and shapes they offer, even though they all seem to be familiar knobbed whelks with their clockwise spiral—not a single counterclockwise lightning whelk among them. Outside they are blue-gray, white or mottled brown; inside, a deep but tender pink. Further along, the whole whelk shells disappear and are replaced by fragments mingled with much more numerous clam, oyster, scallop and mussel. This explains the gatherings of gulls, looking for remains of the shells’ previous occupants; and no doubt, some of the shells are dropped garbage from the birds’ previous meals. I spurn the fragments, as I suppose most people would—we are snobs of the perfect, like the classical Greeks with their circle fetish—and yet broken things have their own magic, especially broken whelk shells, which are like a half-demolished house with the interiors of their rooms exposed. These shells reveal to the outer world the somehow private purplish pink of their interior walls and the slender tubes at the heart of their spirals. Likewise, broken snail shells reveal their spiralling inner chambers, with their outer faces looking like the face of a clock stopped forever.

Wild creatures leave their tracks behind.

Broken and lost things. In Wrotten’s book and the National Seashore Visitors’ Center, there is reproduced a photograph of the stumps of an ancient cedar forest now washed by the surf as the island “migrates” westward. I keep hoping to see this for myself, but there is no sign of it, all the way to the inlet. However, Wrotten wrote forty years ago, and the picture must be older than that; long enough for the island to have further migrated toward the mainland, leaving the remains of the cedar forest to share the fate of Atlantis.

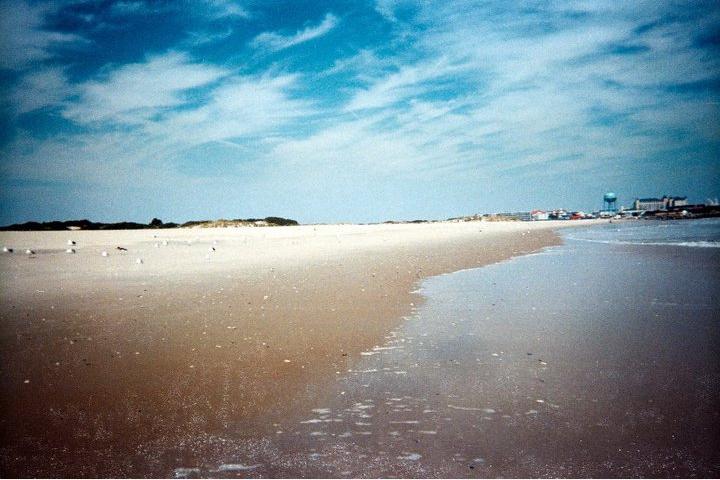

Ocean City is in the center right, and an American oystercatcher can just be glimpsed to the center left.

Trudging further north still, I begin to experience a kind of Zeno’s Paradox effect, as the hotels and Ferris wheels of Ocean City gradually gain greater sharpness and detail, but the line of breakers stretches on and on. Half the distance, and half of half, and half of half of half… Yet I sense, too, that the island truly is beginning to narrow, an almost mystical feeling as if I were approaching the hypothetical vanishing point, with the twin lines of railroad track replaced here by the bay shore to my left and the ocean shore to my right. And yet the breakers are still breaking, the shoreline curving inward here and again to make a shallow bay, then curving back. Half of half of half of half… I enter a zone where the white sand devils appear to have to come to rest, smooth abstract curves of white amid darker sand. Ahead in the northern sky unusually thick swirls of cirrus cloud stand in dramatic contrast to the sharp blue sky – a true sign of autumn, on this hot day.

Just short of the inlet, American oystercatchers with their black heads and long, bright orange beaks join the two or three species of gull in looking for food. The gulls are large and brown, or smaller and a classic gray white, or large again with white heads and black wings. I’m afraid I’m no expert at distinguishing the species. The oystercatchers are shyer of my approach and my camera, and take off with high-pitched squeals when I approach. Also skittish are the little gray-and-white checked piping plovers, rooting around in the wet sand for their portion.

At last I reach land’s end. To stabilize the rapidly eroding north end of the island, the Army Corps of Engineers (which was responsible for causing the problem in the first place by dredging the inlet that opened up in the hurricane of August 1933 and building rock jetties on the Ocean City end that cut off the southward current from carrying its nourishing sand to Assateague) has built a massive seawall of squarish boulders. Boaters pull up in a miniature cove formed by a break in this northward-facing castle wall and wade ashore. This, then, is the somewhat anticlimactic end of this phase of my journey. Now for lunch and the trek back.

Sandy Point, 4 p.m.

The receding tide has left a different world behind it. In several places I have passed miniature overwashes, where by some quirk of topography there must be a slight, hidden bump of sand for the dying breakers to climb over. They succeed and leave behind them shallow, glittering pools of water that the gulls and pipers feast from. As for shells, there are fewer whelks this time—though I found the smallest of those I have ever seen, a perfect, cobalt-colored specimen barely an inch long—but lots of snail shells. I found two or three of the latter with barnacles almost as big as they are attached to them, in different, bright colors—orange to the snails’ dusky blue-gray, say. (When I got them home, I found that the "barnacles" were actually living mollusks that fell off the snail shells as soon as they died.)

One snail shell creaked when I picked it up, as if about to disintegrate, but it turned out to have another shelled creature that had burrowed into its opening, and which I was able to remove with my fingernail. Some of the white scallop shell halves are so thick toward the missing hinge they remind me of fleshy ears. But perhaps prettiest of all are fragments of a certain kind of clam shell, polished smooth by the sea, with white and rich purple striations. In the Torah, the Israelites are instructed to make fringed prayer shawls (tallitot) with “a thread of techelet.” In modern Hebrew, techelet is a light blue, but nobody knows exactly what color it originally refers to—except that, according to tradition, the dye was prepared from a clam shell. The secret long lost, the fringes on modern tallitot are plain white. Separated by continents and millennia, of course the species found on Assateague can’t be the same one, but nevertheless I like to imagine my ancestors proudly wearing the tallit with a thread of rich royal purple.

I shall have to get used to not indulging myself as much as I have on this hike with picking up shells, because when I go on overnights in the “back country” parts of the island near the state line that are inaccessible by car, I’ll have to bring twice as much water and carry my tent and sleeping bag into the bargain.

The wind has picked up again and is blowing steadily from slightly west of south, exactly the direction the island lies in and that I have to walk down. In places, wind and water have worked together to create miniature “cliffs” of sand at the high tide mark, which fall away sharply now that the tide is low. The wind has carved tiny nooks and other detail into these slopes, although perhaps some of the smaller ones are actually dried out air pockets that had been moistened before. There are moments when the stiff breeze creates a pale haze in the distance composed of mingled sea mist and fine grains of sand.

One thing I have not seen on this hike is the Chincoteague ponies. I have seen their dung in a few places, but they seem to shun the northern reach of the island, which grows increasingly narrow and barren of forage as you approach the inlet. I haven’t seen them since this morning, when I spotted a fine herd of seven or eight mostly brown beasts grazing on both sides of the road near the campground.

Back to top

3:00 p.m., Assateague State Park The spattering of rain I drove through on the way here is gone, and has proved to be something of a blessing for walking, since it tamps down the sand all along the beach, making for firm footing. The skies have now partly cleared and the temperature is in the low to mid 50s. On the shoreward side of the dunes there are some small, isolated sprouts of a light green succulent plant. The leaves can't be more than a half inch long and no more than a quarter of that wide at their widest. To the touch, they have the soft, waxy feel one would expect. One of the leaves is so shiny it looks wet. Relatively few gulls are out. A small crowd of fifteen to twenty adults and children are out playing baseball and flying kites as I first emerge from the parking lot of the State Park. 3:20 p.m. The sky to the west-northwest over the mainland is an ominous bruise color, and the breeze is turning chillier. Several yards of the snow fencing meant to protect the fragile dunes from horses and people has blown down and been covered in sand from a winter storm, and unable to resist my curiosity, I walk cautiously up to photograph, being careful where I step for the sake of the plants. Here the succulents are more numerous, sufficiently so to look like a miniature forest sheltering under some taller dried-out plants. 3:52 p.m. Walking south along the shoreline I come to a field of flotsam that looks from a distance like plain dirt or litter but up close proves to be lots of shells and shell fragments, among which little sandpipers and bigger gulls are feeding. So far I have seen only one skate egg case, further back. They look like shiny miniature rectangular black purses, with irregular stems or cords at each corner. Like the fringes or tzitziot that God commanded the children of Israel to wear "at the corners of your garments." Only rigorously Orthodox Jewish men take this to mean that they must wear appropriately fringed undershirts; for others like me, the tzitziot are merely fringes of the tallit or prayer shawl that is worn at morning prayers in the home or synagogue. I confess I have not done much tefillah/davening (prayer) lately. Here on Assateague, though, I always feel God's presence, an admittedly nebulous statement. As I walk on the bruise-colored clouds move in to take up the northwestern-to-northern quadrant of the sky. The wind blows harder and the spitting rain briefly turns into a pelting shower, forcing me to take shelter in the portico of a locked-up bathhouse at one of the State Park campsites. That's where I'm writing this, though by now the shower appears to have passed. I seem to be near the southern end of the State Park campsites, and consulting a map which I am able to download to my "smart phone," I see that I've covered almost half the distance to my destination for the day, the southern end of the National Seashore campsites. Then of course I have to walk back, which I plan to do along the road (which ends at the southern end of the National Seashore campsites), with brief excursions into the marsh and forest on the western, bay side of the island, weather permitting. 4:48 p.m. Entering the National Seashore from the north, I stumble on a fifteen to twenty foot shipwreck, all old timbers and rusting iron, washed by the waves. A park ranger patrolling in an SUV tells me that its provenance is unknown, but it has been catalogued. Signs warn against swimming due to an "underwater obstruction," but the ranger tells me the shipwreck was actually uncovered by the winter storms, and they hope it will be covered up again as the current build the sand up in the course of the summer. He also warns me to watch out for people attempting to pry metal off these shipwrecks, which are numerous along the island. This is illegal; the government of Spain has shown active interest recently in recovering artifacts from these shipwrecks, many of which are Spanish vessels from the great European Age of Exploration. The wind has dropped and the sun has come out intermittently. The sky is still mostly overcast, but at least the bruise-colored storm clouds are gone. 5:28 p.m. Dramatic dark blue clouds from the west again bring rain with them, this time a little harder than before, and I am forced to seek shelter again, this time in some restrooms at a public beach that fortunately are open. I will wait for the shower to pass before proceeding onward. While waiting out the shower I call up The New York Times on my smart phone and read about an Israeli air attack that killed three Hamas "militants" (murderers and terrorists that the Times refuses to call by the proper term, but that's a topic for another day). Thoreau would have been horrified by the relentlessness with which these horrors pursue us even in isolated places of natural beauty, and doubtless I shouldn't have tortured myself in this way by reading about it now. But my I reflect that the same sea booming in breakers beyond the dunes also breaks on the shores of Israel and Gaza. Our world is all one, now more than ever, and there is no escaping this truth. 5:56 p.m., on "Baltimore Boulevard" Emerging from shelter at the end of the last rain shower, I see the sun emerge too, in watery veiled fashion, from behind a gray diaphanous curtain of cloud. The air turns colder. Before long, I enter a stretch of dunes that present a dramatic, even comical aspect in the strange shapes wind and water have sculpted them into. One has a huge notch in it, large enough as it seems, when I draw closer, for a man to sit comfortably in. Perhaps this was created by a wave during a storm, a supposition that gains strength when I walk past a dune several yards behind it, a much more rounded, lower sand hill around which is a sort of dry moat, this clearly excavated by surging ocean waters.Saturday, April 2, 2011: From Assateague State Park to the Dune Trail

|

Marching bayward through this dune country I come to the remains of "Baltimore Boulevard," a road laid out by developers in the 1950s and early 1960s who had dreams of a southern Ocean City, dreams that they convinced some 3,500 people to buy into and which would certainly have come to fruition without the March 1962 nor'easter, which leveled much that had been built, opening the way for state and federal development of an island-wide park, although not without a tremendous political fight, which National Park Service historian Mackintosh described in detail in a 1982 administrative history of the parks. |

The Worcester County, Maryland Board of Commissioners fought tooth and nail against the creation of the National Seashore. In a written statement submitted to the U.S. Senate's Interior and Insular Affairs Committee, which held four days of hearings on the subject in March 1965, the commissioners said, "Worcester County believes that Assateague Island should be privately developed with private capital, initiative, and energy in the American way, and not by socialistic bureaucrats desiring public ownership for the satisfaction of those few who do not have the industry and energy to provide for themselves." The shortsighted meanness of this sentiment speaks for itself. I do not which possibility is more depressing: that the commissioners were corrupted by developers' money, or that they actually believed this Social Darwinist guff. Fortunately, in this instance Congress lived up to its long-term responsibilities to the American people.

Sitting on the crumbling asphalt that the National Park Service has preserved as an object lesson of sorts from this era (as part of its "Life of the Dunes Trail") is a strange experience. The road surface is pitted and grooved by the action of wind and scouring sands, and at its edges it crumbles away in bizarre irregular shapes reminiscent of bluffs and mesas in the desert West. The sight offers food for reflection on what all too often becomes of man's plans where the land meets the sea. The stuff literally crumbles to the touch; Americans do not build roads as the Romans did in several sturdy layers of stone that led them to say with justice in Latin "to fortify a road." Here scrubby evergreens no more than three feet tall, with yellowing needles, are gradually reclaiming the island from the careless builders of fifty years ago.

Walking back to the north from this spot, I am rewarded for undergoing the showers earlier with a pale strip of rainbow, surprisingly close on the right to the westering sun. My eye is caught by brilliant flashes of white through the trees to the west of "Bayberry Drive," the road I am following. I walk about ten yards through the loblolly pine forest and emerge in a clearing where the ground is all white sand. About half an hour later I explore another of these clearings, which seem to be quite common in this part of the maritime forest. The conquest of sand by plants is simply incomplete here.

The walk back seems longer than the walk out took, but this is always the case, and anyway I haven't eaten anything since breakfast except snacks. As sunset draws closer the animal life of the forest begins to emerge. A white-tailed deer ambles into the road twenty or thirty yards ahead of me, but noticing my approach it bounds off before I can get my camera ready, its telltale white tail bobbing in the gathering darkness.

|

All around me is birdsong; a barren tree to my left is occupied by small black birds with crimson stripes on their wings. They fly off at my approach except for one proud bird that sits at the crown of the tree, scolding me. |

While standing in the first sandy clearing I hear a whinny, but it's not until I've been walking north for a while that I first see the Chincoteague ponies, a miniature herd of six of them grazing along the side of the road. I'm alerted to their presence by two stopped cars; most visitors to Assateague act as if the horses are the only wildlife of interest. These brown and white beasts look quite healthy and happy despite having gone through the winter.

Sunset is now definitely upon me and I photograph its change from brilliant orange to deep pinkish red through gaps in the trees caused by tidal creeks. No specific blessing for seeing a beautiful sunset comes to mind, so I recite one from the shacharit, the Jewish matins—"Blessed are you O Lord our God, King of the Universe, who opens the eyes of the blind." For this gift of truly seeing, I thank You, O Lord. An owl calls through the trees as the sun disappears.

11:33 a.m., near the southeastern corner of Toms Cove

I run into a couple in their early 60s who honeymooned here 39 years ago. The man points out to me a yellowish piece of coiled flotsam a foot and a half long that is segmented like a dryer exhaust tube, although the individual segments are solid and look white as sliced potatoes inside. These are whelk egg cases.

The shore is alive with sandpipers that have a habit of folding one leg up and standing or hopping on just the one leg. Their beaks look a good three inches long, narrow and needlelike for probing for prey, and their trill is high-pitched, like a speeded-up bleat. When they take off, they display wings striped dark gray and white.

|

This is young country, pioneer territory. The entire hook has grown up only in the past century or so, the sand deposited by southward-tending currents. It is barren except for dunes, and no more than fifty yards across east to west, from ocean to cove. Much is roped off and access forbidden, because this is prime nesting territory for the endangered piping plover, Charadrius melodus, as well as the least tern, Sternula antillarum, and the black skimmer, Rhynchops niger. |

12:00 p.m.

The barren portion of the hook I have just walked down looks on a map like bare bone, but at its southern end it bends westward toward the mainland, and this part looks thicker and fleshier. The dunes are higher here and there is an covering of brush in places over the bare sand.

Today is much sunnier than yesterday, and warmer, with temperatures in the mid-to-upper fifties that can feel even warmer if you are sitting in the lee of a dune, as I am now, writing this.

The sea is quite calm, the waves hardly any bigger than those I have seen on the enclosed Mediterranean. Driving over from Chincoteague, the water in Assateague Channel was a deep blue-green, considerably darker than it was when I crossed Sinepuxent Bay over the Verrazano Bridge yesterday afternoon. Then the water was almost a pale jade color.

12:39 p.m.

| Two treasures since my dune break! I found a sand dollar with a five-pointed pattern imprinted on it. It looked iridescent purple when I forst picked it up, but as it dried it faded to light gray. I've read that this happens with beach pebbles because the seawater fills their myriad small scratches, so you can change them from dull back to lively by putting them in water or rubbing them with baby oil. I might try a clear shellack. |

Gray seal (Halichoerus grypus)

And then I see a seal! The ranger I talked with yesterday about the shipwreck mentioned that gray seals (Halichoerus grypus) and harp seals (Pagophilus groenlandicus) have been seen on the Assateague beaches lately, but he warned me not to approach them too closely, because they bite. I kept a respectable distance from this one as he used his flippers to crawl back into the water. He was a shiny medium gray.

1:17 p.m., Assateague's southernmost extremity.

Harp seal (Pagophilus groenlandicus)

Here once again I am in a barren, flat land of sand. A partly dried channel of gray, lumpy sand shows where seawater flowed just recently, behind that, two large pieces of driftwood make an acceptable makeshift bench. After encountering the gray seal, I had an even closer encounter with a pale-faced harp seal, who showed no fear as I came within five feet of him to take my pictures. He just gazed at me with his liquid dark eyes.

2:06 p.m.

The southern hook of Assateague is a treasurehouse for all kinds of things, notably the shells of the knobbed whelk (Busycon carica) that the currents dump here in their hundreds, along with the sand. Also the piping plovers themselves, skittering along at the edge of the surf and probing for food as they go. Overwashes are common here, sometimes producing shallow standing pools of water that heat up fast in the sun. Over the exposed sands of this corner of the island, the wind blows steadily.

These overwashes show how in nature the small adumbrates the large, and the large the small. The temporary pools of water empty back into the sea through breaks in the sand, down which water flows just as in the longer-lasting tidal streams known as guts. Another example from the ocean beach is the miniature "cliffs" of sand six to eighteen inches high at the dunes' edge created by wind and water, which display darker and lighter layers of sand in cross section, like tiny Grand Canyons. The same geological forces that shape the continents are at work on the humblest spit of sand.

|

3:15 p.m.

I made my way through the knobbed whelk shell paradise. There are also shells of the lightning whelk (Busycon contrarium) here, the difference being that their spiral is counterclockwise and their opening is on the left. I've only ever found one of those, and today I don't see any. I pick my through the knobbed whelk shells, trying to be selective since my collection has already grown to the point where I can't possibly display it all. So I look out for shells that are unusual in some way, such as a tiny bleached white whelk shell less than half an inch long, or with richer interior colors. |

|

The sandy beach begins to give way to rich mud flats, seagulls foraging in the rich sulfur-smelling stew where myriads of shells lay scattered. Here many of the shells are broken or bleached white or both, as they slowly disintegrate, releasing their calcium back into the environment. The bay water separating the island from the mainland comes in bands of dramatically differing colors, pale blue-green alternating with near-cobalt. |

Walking along, I find the occasional water bottle or other bit of left behind litter. I feel guilty not picking these up, but I have no way of carrying them with my other things. And yesterday I lost a flip-flop, and now just as I was writing these words one of the gallon storage bags I use to protect my keyboard blew away, tumbling end over end through the mud flats as I futilely chase it, so I'm afraid I too have littered, if inadvertently.

Great egret (Casmerodius albus)

Walking back, I glimpse over the dunes a pair of American oystercatchers (Haematopus palliatus) with their black heads and long, bright orange beaks foraging in the cove. After picking up my car, I drive back toward Chincoteague, stopping to observe some great egrets (Casmerodius albus) fishing in some deep channels near the road. Then I visit Assateague Lighthouse, which stands some 100 to 200 yards north of the northern bank of Toms Cove, at what used to be the southernmost tip of the island, before the littoral currents created the hook, as maps on display outside the building show. Nevertheless, the lighthouse is still in use, its beam sweeping around in the darkness just as it did 150 years ago.

|

Looking through a viewfinder at the top of the rise where the lighthouse stands in the direction of the cove, I spot what I think is a great blue heron (Ardea herodias), although pictures I look at later make me somewhat doubtful that the big bird with the tuft atop its head that I saw was actually that species. As I walk back to my car an owl hoots a farewell though the loblolly forest. |

The following day I talk with another frequent visitor to Assateague, who remembers finding red starfish and "spider conches" washed up on the beach after a hurricane. These Floridian creatures couldn't survive in the colder waters so far from their subtropical habitat. Like me, he enjoys the solitude the island offers, and likes to go there in the rain when most tourists would flee.

|

Home |

Copyright © 2011, Martin Berman-Gorvine